What is Saffron?

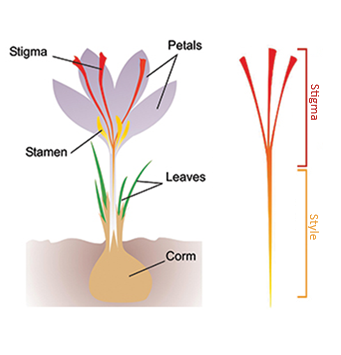

To appreciate why saffron is considered the rarest and most precious spice, it helps to first understand the anatomy of the saffron flower, which is derived from the Crocus sativus plant. This plant is a sterile triploid, meaning it cannot reproduce via seeds due to its genetic structure. Instead, it multiplies asexually through the division and propagation of its underground corms.

Key Anatomical Features

Below is a concise overview of the saffron flower’s main anatomical components:

-

Flower Structure

The saffron flower is a delicate, cup-shaped bloom, typically pale purple or lilac, featuring six petals arranged in two whorls. These petals are uniform, lending the flower a symmetrical appearance

-

Stigma

The most vital part for saffron production, the stigma is the female reproductive organ, comprising three vivid crimson-red threads (filaments) that extend from the flower’s centre. These stigmas are hand-harvested and dried to produce saffron spice, prized for its flavour, aroma, and vibrant colour.

-

Style

The style is a slender, pale-yellow tube that connects the stigma to the ovary. It supports the stigmas and, in fertile plants, would channel pollen to the ovary during reproduction (though this is non-functional in Crocus sativus due to its sterility).

-

Stamens

The flower contains three yellow stamens, the male reproductive organs that produce pollen. These are shorter and less prominent than the stigmas

-

Leaves

The flower emerges from narrow, grass-like green leaves that grow from the base of the corm. These leaves facilitate photosynthesis and are present during the flowering season.

-

Corm (Underground Bulb):

Although not part of the flower itself, the underground corm—a bulb-like structure—serves as the plant’s storage organ. It is the source of the flower and leaves and is crucial for the plant’s perennial growth cycle.

Asexual Multiplication

Having outlined the flower’s anatomy, let’s revisit its unique method of asexual reproduction. Unlike many plants that rely on seeds, Crocus sativus propagates through its corms. After flowering in autumn, the mother corm produces smaller cormlets (daughter corms) around its base. These cormlets develop into mature corms over time, enabling the plant to multiply clonally. Farmers typically dig up and separate these cormlets after the growing season (late spring or early summer) for replanting, ensuring optimal conditions for the next crop.

Regional Varieties

Saffron, derived from the Crocus sativus plant, is cultivated naturally in the soil across numerous countries using traditional agricultural methods. As per the most recent estimates, the following nations are recognised for growing saffron through these time-honoured practices:

Iran

The world’s leading producer, accounting for approximately 88–90% of global saffron output. Annual production estimates range from 190 to 430 metric tons, with 336 tons reported in 2020 and over 300 tons projected for 2025. Variability arises from climate challenges and unrecorded local consumption.

India

Predominantly cultivated in Kashmir, production is estimated at 6–25 metric tons per year, with figures of 18–22 tons in recent years (e.g., 22 tons in 2019). Domestic demand often outstrips supply, leading to imports to meet needs.

Afghanistan

An emerging producer, with output rising from 20 metric tons in 2022 to 46–67 tons in 2024, fueled by government support and increasing export opportunities.

Greece

Produces around 6–10 metric tons annually, with the Kozani region serving as a key cultivation area, though exact figures fluctuate year to year.

Spain

Yields approximately 1.5–15 metric tons per year, with the La Mancha region playing a significant role, though production has declined from historical peaks (e.g., 450 kg in 2022).

Italy

Generates about 0.6 metric tons annually, primarily from Sardinia, though some saffron is imported and reprocessed locally.

Turkey

Estimated at 2–3 metric tons per year, with growing interest in saffron cultivation in recent years.

France

Production is minimal, likely less than 1 metric ton, with small-scale efforts in specific regions.

Switzerland

Very limited output, with only a few kilograms produced annually (e.g., in Mund village).

Pakistan

Features small-scale production, estimated at less than 1 metric ton per year.

China

An emerging producer, with output likely below 1 metric ton annually, concentrated in regions like Xinjiang.

Japan

Minimal production, likely less than 0.5 metric tons per year.

Australia

Small-scale cultivation, with production estimated at less than 1 metric ton annually.

United States

Primarily grown in Pennsylvania, with minimal output, likely under 1 metric ton per year.

It is clear that Iran dominates the global saffron market in terms of volume. However, Kashmiri saffron from India follows as a significant contender, distinguished not by quantity but by its superior quality, which often surpasses that of Iranian saffron.

Why Kashmiri Saffron Stands Out

Kashmiri saffron, is widely regarded as the finest saffron available, outshining all other varieties, including those from Iran. Its exceptional quality stems from the unique high-altitude climate of Kashmir, organic cultivation practices, and meticulous hand-processing, which enhance its deep red colour, intense aroma, and robust flavour.

Notably, Kashmiri saffron boasts the highest picrocrocin content—often exceeding 13% of dry matter—contributing to its superior bitterness and taste, a key quality marker under ISO 3632 standards. This surpasses the average picrocrocin levels of even the best Iranian grades. Additionally, its slow sun-drying process preserves a higher concentration of active compounds, such as crocin and safranal, making it unmatched in culinary and medicinal applications.

While Iranian saffron dominates in volume, Kashmiri saffron’s unparalleled quality, backed by its Geographical Indication status, positions it as the best saffron globally, justifying its premium status over all other regional varieties.

Picrocrocin

Picrocrocin is a naturally occurring glycoside compound found predominantly in the stigma of the Saffron flower. It plays a crucial role in defining saffron’s unique sensory profile and is a key indicator of its quality. Below is a detailed explanation of picrocrocin, its chemical nature, function, and significance.

Chemical Composition and Structure

Picrocrocin (chemical formula: C16H26O7) is a bitter-tasting glucoside, consisting of a sugar molecule (glucose) attached to a terpene alcohol called safranal glycoside. Its molecular structure includes a glycosidic bond that links glucose to a derivative of the terpene cymene. During the drying and storage of saffron stigmas, picrocrocin undergoes enzymatic hydrolysis, breaking down into D-glucose and safranal, the latter being the primary volatile compound responsible for saffron’s characteristic aroma. This transformation is a natural process that occurs as the fresh stigmas are processed into the dried spice.

Role in Saffron

Flavour Contribution

Picrocrocin is the primary source of saffron’s bitter taste, which is a distinctive and highly valued sensory attribute in culinary applications. This bitterness enhances the complexity of dishes, balancing the spice’s sweetness and earthiness derived from other compounds like crocin

Quality Indicator

The concentration of picrocrocin in saffron is a critical measure of its quality, as standardized by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO 3632). This standard assesses saffron’s potency through spectrophotometric analysis, measuring absorbance at 257 nm, where picrocrocin absorbs light. Higher picrocrocin levels indicate a more robust flavour profile and higher health benefits

Precursor to Safranal

As picrocrocin breaks down during drying or storage, it releases safranal, which contributes to saffron’s hay-like, floral scent. This dual role makes picrocrocin a foundational compound for both taste and aroma.

Factors Affecting Picrocrocin Content

Growing Conditions

Regions with high altitudes, such as Kashmir, and optimal climates (e.g., Mediterranean areas) tend to produce saffron with higher picrocrocin levels due to increased UV exposure and cooler temperatures, which enhance metabolic activity in the stigma.

Harvesting and Drying

Hand-picking at the peak of flowering and slow, controlled drying (e.g., sun-drying in Kashmir) preserve picrocrocin, while over-processing or improper storage can reduce its concentration through premature hydrolysis.

Regional Practices

Variations in cultivation and post-harvest techniques across countries like Iran, India, and Greece influence picrocrocin levels, with Kashmiri saffron often cited for its exceptional retention due to traditional methods.

Significance in Culinary and Medicinal Use

Picrocrocin’s bitterness is prized in cuisines worldwide, adding depth to dishes like risottos, paellas, and desserts. In traditional medicine, saffron’s bitter compounds, including picrocrocin, are believed to aid digestion and have antioxidant properties. The compound’s stability during cooking also makes it a reliable flavour contributor, unlike safranal, which can volatilize under heat.

Conclusion

Picrocrocin is a vital component that distinguishes high-quality saffron, linking its bitter taste to its prestige. Its presence, alongside crocin and safranal, defines the spice’s sensory and commercial value, with levels varying based on geographic and processing factors. As per the most recent data, ongoing research continues to explore its biosynthesis and potential health benefits, reinforcing its importance in the saffron industry.